Cameroon

| Attachment | الحجم |

|---|---|

| GISW2010CountryCameroon_EN.pdf | 1.98 MB |

Organization

Website

Introduction

Our society has entered an era where information and communication, previously conveyed by means based on fairly renewable resources (paper, words, etc.), now use "electronic" conveyors.

Information and communications technologies (ICTs) have an image of being "clean technologies". They can be a catalyst for the development of poor countries. Given the impact of their use in rich countries, it is certain that Africa can prosper thanks to these technologies. The current problem is that they consume energy, produce more and more waste which is difficult to treat,1 and spread toxins impossible to recover.

According to United Nations (UN) statistics, electronic waste (e waste) amounts 20 to 50 million tonnes per year globally. And a Greenpeace report claims that half of this “electronic junk” is sent to the developing countries. 2 In Cameroon, the government’s commitment to improve access to new ICTs in order to reduce as quickly as possible the digital gap between the North and South, has resulted in the arrival in the country of hundreds of thousands of second-hand computers with a reduced life span. This has contributed significantly to an increase in e waste.

What becomes of them? Who is in charge? What are the channels for distribution and disposal? What are the contributions and responsibilities of different actors, companies, local authorities, associations or consumers? Is there a danger of pollution? Do these computers contribute to the fight against the digital divide?

There are many questions to which we need to find answers. The objective of this report is to begin to shed light on the environmental aspects of digital infrastructure in Cameroon, focusing on the management of e waste.

National policy

The Cameroonian policy landscape on e waste is still very poor. In fact, e waste is given very little or even no attention in our country. The National Waste Management Strategy is the sole body of rules broadly dealing with waste. The strategy lays out principles such as the principles of sustainable development, the principle of “polluter pays”, the principle of equity and the right to information, and that the public should be aware of the dangers of dealing with waste. These principles derive from Law No. 96/12 of 5 August 1996, dealing with environmental management in the country.

Legislative context

There is no specific legislation dealing with e waste in Cameroon. Nevertheless, various laws can be read to impact on e waste. First of all, the country’s constitution, in its preamble, states that: “Every person shall have the right to a healthy environment. The protection of the environment shall be the duty of every citizen. The state shall ensure the protection and improvement of the environment.”

Secondly, Law No. 89/027 of 29 December 1989 deals with hazardous and toxic materials, 3 mainly in its Article 42. Thirdly, Law No. 96/12 of 5 August 1996 deals with the legal framework for environmental management.

Cameroon has also ratified the Basel Convention4 (on 11 February 2001) and is part of the Bamako Convention related to the prohibition of importing hazardous or toxic materials into Africa.

Overall, Cameroon’s legislation has yet to deal properly with hazardous waste. The National Waste Management Strategy concerns itself primarily with categorising waste, but has not looked specifically at how to sort out different kinds of wastes such as plastics or e waste.

E-waste entering the market

Cameroon does not manufacture ICT equipment; the country imports these products through various channels.

While there are the regular importers, which work via other African countries, countries in the Middle East, Europe and the United States, a lot of equipment comes into the country as a result of migration to other African countries and throughout the diaspora. The informal market is supplied by the equipment sent by families residing in Europe or the United States to their relatives, after first use.

Moreover, thousands of "obsolete" computers pour into the country disguised as donations to institutions, NGOs and associations. In 2003, World Computer Exchange (WCE), an NGO working in the educational sector, delivered, via the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), containers of 200 to 400 second-hand computers. 5 In 2007 the organisation Computer Aid International sent a large number of recycled computers to Cameroon (some 44 containers with 225 computers in each).

According to Cameroonian customs authorities, the import of new and second-hand computers into the country was estimated to be 3,949 tonnes in 2007 and more than 6,240 tonnes in 2009. However, this does not distinguish between new and used computers. But, from observation, most of these computers are used, given the large number of flea market stalls selling second-hand computers in Cameroon.

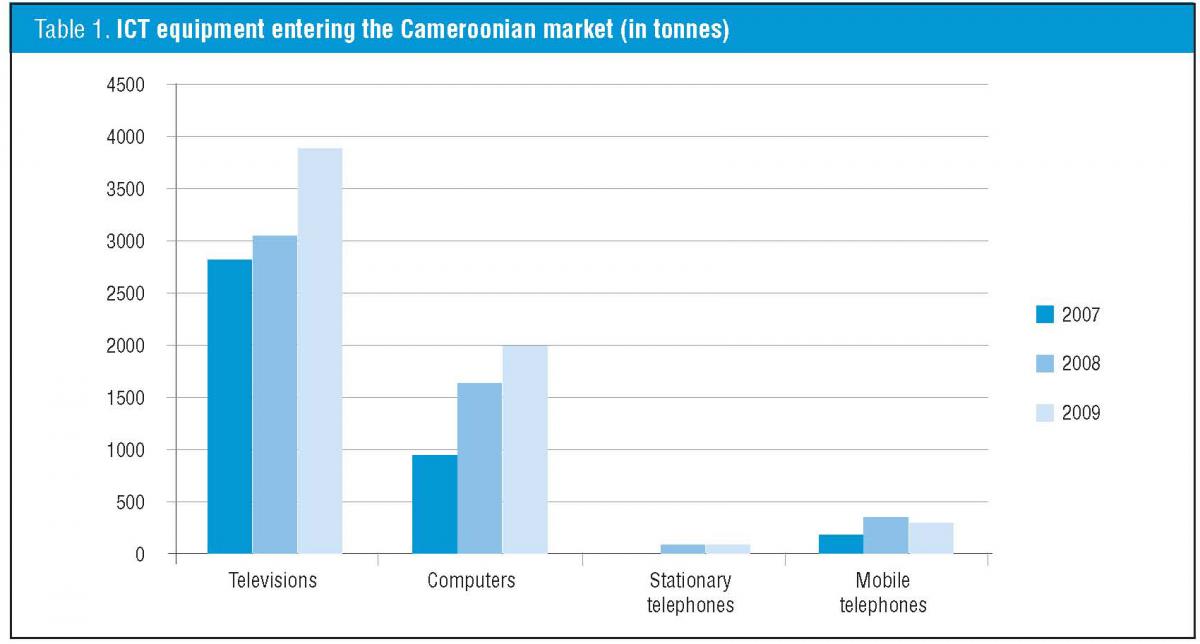

Table 1 shows the distribution of total tonnage of ICT equipment put on the market, by category and year (based on figures from Cameroonian customs).

Table 1. ICT equipment entering the Cameroonian market (in tonnes)

The data recorded at customs reflect a global trend of increasing imports of computers, televisions and mobile phones, of about 33% overall. This may increase to more than 40,000 tonnes of e waste entering Cameroon in the years to come.

Market exit

End-of-life technology becomes e waste if not repaired or reused. It then changes its status from second-hand or third-hand "product" to "waste". Some of this waste is stored in offices, government buildings and homes. Some is sent to landfills or incinerated, which affects the environment and health.

In Cameroon, the amount of end-of-life equipment is increasing, because of an increase in the number of users, but also because most of the products bought are second-hand.

According to Law No. 96/12 of 5 August 1996 concerning the legal framework on environmental management, waste "is considered any residual waste from a process of production, processing or use, any substance, material, product, or more generally any personal property abandoned or that the holder intends to discard.”

Following discussions and debates related to the classification of waste, a typology for a waste management strategy was adopted that included:

- Household and similar waste (municipal solid waste, toxic waste in dispersed quantities, liquid household wastes, sewage, and gaseous wastes).

- Industrial, commercial and artisanal waste.

- Hospital waste.6

The average production of general waste per person per day is between 500 g and 600 g in Cameroon. As a result, the daily quantity of solid household waste products throughout the territory is estimated at 9,545 tonnes for the total population (17,354,431 inhabitants), or a total of 3,483,902 tonnes per year. 7

Although no legislation deals specifically with e waste, it is found predominantly amongst industrial and commercial waste, as well as, to a degree, in household waste. According to our interviews, repairers discard little of their e waste for fear that the owners of the devices they have repaired may come back to claim the discarded waste. Similarly, it is difficult to get households to clear out their e waste because of the perceived value of old technology, and the high cost of new technology.

Reuse

The systematic reuse of discarded technology is difficult without an effective collection system. 8 On the other hand, be they computers, televisions or mobile phones, they are recovered by some business, for instance Popular Electronics, where training occurs on the job. Their tools are basic: a screwdriver, brush, tongs, wax and soldering iron and, for the richest among them, a tester, which is more or less reliable, to ensure the refurbished equipment works well. Circuit boards are stored for easy reuse, and equipment is repaired several times before being finally abandoned.

Recovery and recycling

In Cameroon, plastic casing for things like computers is burned or discarded. There is no capacity for metal recycling. We also did not find any smelting activities to reclaim metals such as in other emerging countries like South Africa or China. Toxic compounds and precious metals have no other fate than ending up in the environment, with the consequences that follow.

End-of-life mobile phones are often found in rural areas. Old casings and used-up batteries are often found in the street, or on landfills where waste pickers collect them. The current waste management system is not suited to this type of material. It is created, rather, for the management of biodegradable waste or solid waste (i.e. construction materials).

Given the problems posed by the inclusion of e waste into the general waste stream in Cameroon, the consequences must be taken seriously. The management of e waste in Cameroon is still in its infancy, and there remains much left to do.

Impact on health and the environment

Unfortunately there are no mechanisms in Cameroon to monitor and fully appreciate the problems posed by e waste on health and the environment. Furthermore, no study on the problems posed by e waste in Cameroon has yet been conducted. However, we believe that the data on the health and environmental impacts of e waste generally apply perfectly to Cameroon. As a result, areas where there is the public disposal of industrial waste are strongly suspected of being contaminated by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Examples of these areas include the Ngousso “open pit” (Yaounde), and sites at Makepe (Douala) and Nkolfoulou (Soa Yaounde). 9

Impact on the economy

It is difficult at present to determine the economic impacts of the e waste sector. No studies have been conducted on the pollution level at the collection sites to determine the possible costs of decontamination.

Otherwise, this industry has had positive economic impacts by improving incomes through job creation. There remains potential to integrate actors of the informal sector into the recovery and recycling of e waste.

It is true that Africa generally, and Cameroon in particular, should not be a dumping ground for unusable second-hand equipment, but given the standard of living of the population and the political will of governments to fight the digital divide in order to develop the continent, would this second-hand e waste not be an asset to exploit? Particularly if some measures are taken on setting up structures for both reuse and recycling?

Action steps

Given the results obtained from our research, and in order to work towards a better understanding and management strategy of e waste and its damage to human health and the environment, we propose:

- Lobbying actors in charge of waste management in Cameroon to develop an appropriate national policy, regulatory and legislative framework for e waste.

- Lobbying the government for the establishment of an official system of collection and storage of e waste to help with monitoring and environmentally sound disposal.

- The systematic sensitisation of different actors on the dangers posed by e waste. The promotion of collaboration between the public and private sector and the involvement of civil society in the development of an effective education programme.

- Strengthening the technical capacities of resource persons to conduct an inventory of e waste with the view of elaborating sectoral strategies and plans for managing e waste in Cameroon.

- Conducting a study of certain public dumping sites, and repairers’ workshops, to better appreciate the impact of e waste on workers in these places.

Notes

1 Finlay, A. (2005) E-waste challenges in developing countries, APC, Johannesburg.

2 Cobbing, M. (2008) Déchets électroniques: Pas de ça chez moi, Greenpeace France, Paris.

3 The law states that waste will be dealt with to reduce its harmful effects on human health, the environment and natural resources.

4 The Basel Convention seeks to restrict the movement of hazardous waste between countries, specifically from developed to developing countries. It is also concerned with waste minimisation and the environmentally sound management of waste.

5 UNESCO (2003) Rapport final de la première réunion internationale des spécialistes sur les nouvelles synergies pour le recyclage des équipements de technologie de l’information, Paris, 14-15 March.

6 Government of Cameroon (2008) Stratégie Nationale de Gestion des Déchets au Cameroun (période 2007-2015).

9 CAPANET (2005) Les Polluants Organiques Persistants (POPs) au Cameroun.