Ivory Coast

Report Year

| Attachment | Tamanho |

|---|---|

| cote_divoire.pdf | 1.42 MB |

Organization

Website

Ce rapport est disponible en français.

Yasmina Ouégnin: A strong “NO” that leads to a stronger “YES” for women's rights

Introduction

Also known by bloggers and football fans as “Drogba's country”, Côte d'Ivoire is the “mini” West Africa of West Africa. With a high rate of immigration from neighbouring countries, its population of 21 million is a consistent ethnic mesh that dates farther back than the early 1960s. The youth population is one of the highest in Africa. In 1988, only 4% of the population was classified as “aged”. The level of education has been rising slightly over the years and currently stands at 24% of the population with post-high school enrolment.

Orange, white and green are the national colours – the green aptly representing not just the lush vegetation of the south and the green grasslands of the north, but equally agriculture, which is the economic mainstay of the country. In this, the men handle the key crops: coffee, cocoa, cashews, oil palm, cotton, bananas and plantains, which are mainly for export. The women cultivate vegetables, yams, cassava and other food products, mainly for national consumption.

On the political front, much has been written about the 1960-1970 years of economic boom in the country, which were followed by an economic downturn, political crisis and finally civil war. The country has started on its way to recovery and key data are gradually moving from red to green. The Bretton Woods institutions are foreseeing greater growth in the coming years. The present government, made up of 28 ministers, out of which five are women, predicts that the country will be among the “emerging economies” by 2020.

Noticeable in its resurgence is an increase in citizen engagement through social media. Having used the internet as a major enabler during the post-election crises, both leaders and citizens have come to accept the “internauts” as a living, thriving part of the society, as well as the internet’s capacity to give men and women fair access to services, opportunities and the power to engage.

As one of the more upward-looking nations in terms of women's rights, Côte d'Ivoire has come under the international limelight after its war. The vice presidency of the national assembly has been reserved for women, and the post of the national grand chancellor has also been handed to a woman. Nevertheless – and even though it is inherently a matriarchal nation, owing to the Akan[1] ethnic groups that make up over 40% of its population – women’s rights have yet to make a full comeback.

Yasmina Ouégnin

It is in this context that Yasmina[2] Ouégnin emerged to embody, from a certain perspective, the “new Cote d'Ivoire”. In her early 30s, she holds a post-graduate degree in risk management and is the general director of a company in Abidjan. Also a mother, she speaks French and English. She grew up in the opulent Cocody Commune, which is the high-end part of Abidjan. Her father has been a national personality in Cote d'Ivoire, having served the first and second presidents of the republic as the chief protocol officer. Her name, therefore, does not go unnoticed.

Bonjour to Yasmina on social media

In 2012, the government of Côte d'Ivoire finally got around to convening the electoral college to hold legislative elections. The last elections had been held in 2001, and the official terms of the members of parliament had ended in 2006. After that, the country was in a legislative limbo. So, in 2012, there was a real electoral fever across the nation.

That was when Yasmina rose through the social media limelight, with her official Facebook page and two Twitter accounts. She was open, engaging and very personal in her communications with Ivorians. She was seeking election as a member of parliament for the Cocody Commune district, representing the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI).

The “internauts” of Cocody Commune and the national online community in general were enamoured by her youth, her beauty, her openness and her capacity to engage people. She shared her daily schedule, uploaded pictures, answered questions and shared information. But there was great doubt about her age, and her capacity to pull through in the elections. She did, and became one of the youngest members of parliament in the country’s history.

Au revoir to Article 53 and major changes to a group of related laws

One of the major constitutional revisions that were undertaken by the newly elected parliament concerns the family. The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry for Family, Women and Children Affairs suggested the abolishment of Article 53 of the Family Code, and in consequence alterations to Articles 58, 59, 60 and 67 of the same code.

What did they say? What was to change?

Article 53 states that both spouses shall contribute to family expenses in proportion to their respective capacities. In the event that any spouse refuses this obligation, s/he may be obligated by a court of law to do so. Article 58 states that the husband is the head of the family. He exercises this function in the common interest of the home and children. The wife supports the husband in ensuring the moral and material direction of the home. She cares for the home, raises the children and sees to their well-being. The wife replaces the husband in the event that he is unable to play his role as the head.

In keeping with the above, Article 59 states that the husband is the principal breadwinner of the family. He has an obligation to provide for the economic needs of the wife according to his capacity. If he does not fulfil this obligation, he may be obligated by a court of law to do so. Article 60 states that the choice of residence for the family is made by the husband and the wife is obliged to live there. Article 67 states that a wife may engage in a profession different from that of the husband as long as the profession is not contrary to the interest of the family.

On 26 September 2012, the government voted to change these articles. In its note of intention, the government explained that the reasons behind the changes were:

- A drive for shared responsibility of spouses in marriage, conferring to both the equal moral and material direction of the family

- The need for both spouses to contribute to family expenses

- To secure a common agreement in the choice of a residence

- To allow both spouses to freely choose a profession

- To spur the autonomy of women

- To conform to international standards.

Following the decision, Article 53 was annulled. Article 58 now states that both spouses jointly head the family in the common interest of the home and children. They shall both cater to the moral and material needs of the family, provide for the education of the children and ensure their future. In keeping with the above, Article 59 now states that both spouses contribute to the family expenses according to their respective capacities. If one spouse does not fulfil this obligation, the other may seek and obtain authorisation from a court of law in their residential precinct. Such authorisation will allow the spouse to receive a portion of the salary or revenue earned by the other spouse for the needs of the home.

Article 60 now states that the choice of residence for the family is made by both spouses. In the case of a disagreement, a court of law shall decide for the common interest of the family. Finally, Article 67 now states that both spouses are free to choose their profession as long as the profession is not contrary to the interests of the family.

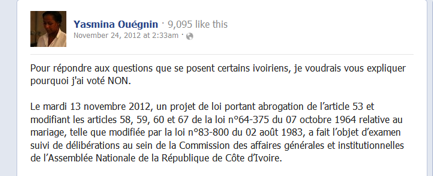

The government tabled the text for approval by the members of parliament at the national assembly. It was submitted to a vote on 21 November. The debates were long, hard fought and unprecedented. Contrary to expectations, Yasmina voted “no”. On 24 November she posted an 894-word explanation of her reasons on Facebook and signalled on Twitter that any of her constituents who were interested could read her reasons there. The article received 370 likes, 97 shares and 221 comments on Facebook alone.

What were her reasons? Basically these:

- Proposals from a member of parliament to amend the government’s text were rejected. It was either take it or leave it. She felt that the essential work of the legislative body was being done by the executive.

- The notion of a “head” is inherent to the Ivorian nation. In all domains of life, there is a clear leader. Removing this notion from the family does not necessarily contribute to furthering the rights of women.

- Laws that have been adopted since independence on the protection of women and children, especially in the areas of domestic violence, female genital mutilation, the right to education and health, child trafficking and child soldiers, have yet to be fully operationalised. She felt the current amendments would go the same way.

- On the day of the vote, she felt that the parliament was being pressured to adopt the executive’s decisions.

The so-called “Non de Yasmina” (Yasmina’s No) debate took off on her official Facebook page, on her personal Facebook page, on Twitter and across the social media spaces in Côte d'Ivoire. Her reasons were argued over and over again. Some citizens thought that for such landmark legislative decisions, members of parliament should have held town hall meetings and heard from their constituents. They wanted a voice.

Though some disagreed with Yasmina's position, they did agree that the process of the adoption of the law itself endangered its application. The overwhelming consensus was for there to be more openness, more transparency and more consultation. Yasmina became a champion for online and offline communities in citizen engagement in legislative and democratic processes. She accepted the role, informing us via Twitter and Facebook of all the issues that she believes are important to the citizens.

In March, when the electoral college was informed of regional and county elections that would be held in April, some citizens decided to approach Yasmina with an initiative that had never been seen in the country since its independence: a face-to-face debate between the mayoral candidates in the Cocody Commune. She set to work on this initiative and on 15 April, the good news came: “Of the nine candidates contacted, five have confirmed, and two are considering. The debate will take place on Thursday the 18th, at 7 p.m. at the County Hall.”

The news went viral: unprecedented citizen mobilisation was underway. The announcement received 50 shares on Facebook alone. The #Cocody hashtag on Twitter also came alive. A youth organisation volunteered to offer free logistics services. Bloggers volunteered to live-tweet the debate, and an online TV service took up the challenge of live streaming. The debate went well, and was followed by thousands online and via live streaming. The ensuing discussions and media coverage are still flowing. It is expected that for the next elections in Côte d'Ivoire, the town hall debate will become mainstream.

Bonjour to issues

The “Non de Yasmina” debate has shone a spotlight on women’s rights issues as well as others. She herself raised some of them. The biggest is the role of the legislator in the policy process. Among other issues in her explanatory note on Facebook, Yasmina referred to her impression that due to party politics, parliament was being constrained by a situation where it may only serve to rubber stamp bills proposed by the executive.

The other issue was the operationalisation of laws that have already been adopted. Is it enough to pass bills into law and not establish the framework for their execution? How have laws that affect the rights of women been tracked, monitored, evaluated and reported? How is the country doing in relation to laws that have been put in place: access to education and health, female genital mutilation, domestic abuse, etc.?

Widespread consultation on women’s rights laws is also a challenge. It is not clear that there was any kind of consultation before the cancellation of Article 53 and proposed changes to its related laws. There are indications that many citizens only heard about the bill when it was about to be tabled before parliament for approval. Even at that stage, members of parliament did not consult their constituents. There was a clear consensus on many social media platforms on that one point.

What exactly changed with the new framing of the law? What remained? Did the citizens understand these changes? The answer is “no”. The one message that most people understood was “now men and women are both heads of the family and they both pay the bills.” Given that the law was voted on towards the end of the year, many men exercised their “legitimate” right not to buy gifts for their partners, since they had also become a co-head of the family. In the long run, such an understanding will end up being detrimental to women.

Quo vadis?

Where do we go from here? What can we do and how can we do it? Among other steps, it is important to:

- Use the internet to establish an observatory of women’s rights. It is important to track laws that exist, their implementation and their outcomes.

- There is a great need for more consultation with the population. Members of parliament, like Yasmina, need to consult their constituents. Social media networks have proved their capacity to make this happen at little or no cost.

- Though there is increased openness in legislative procedures in terms of live broadcasting and streaming of key sessions of the national assembly, more work needs to be done in this area.

- There are civil society organisations working on the promotion and protection of women’s rights. They need to be trained to be able to mainstream the use of the internet in their work.

Overall, we need more Yasminas who can say “no” so that when we finally say “yes” it will be strong, resolute and sustainable.

References

[1] The Akan ethnic groups include the Baoulé, Nzima, Ebrié, Attié, Abbé, Bété and other smaller groups in the south, east and central regions of the country

[2] Fondly addressed as “Yas” by many online.